23-25 June 2023. Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines.

The DOST Forest Products Research and Development Institute (DOST-FPRDI), hosted the workshop Guro, Kawayan, at Musika: A Training on Bamboo Musical Instruments Making and Tuning. This is part of the Bamboo Musical Instruments or BMI Innovation Research and Development Program. After successfully studying various bamboo music cultures across the Philippines, bamboo materials, researching applicable processing technologies, creating prototypes, and designing learning modules for the K12 classroom, they continue the legacy through various workshops and trainings in instrument making.

Along with MAPEH and music teachers from Region IV-A and the National Capital Region, the UP Center for Ethnomusicology (UPCE) was invited to send participants. Representing the center were James Dan Gazmin, Junior Library Aide and UPCE Instrumentarium Assistant, and Benedic Justine U. Velasco, Junior Office Aide for the UPCE Audio Conservation Laboratory.

The workshop was held at the BMI Processing Center of the DOST-FPRDI, within the green and sprawling UP Los Baños campus, a fitting backdrop to the nature of the workshop - bamboo instrument making. Over the course of the three-day workshop, the participants were introduced to various processing technologies that would help in improving the sound and increasing the longevity and durability of the bamboo instruments. These are the results of the research done by the BMI program. Truly, a marriage of science and music.

On the first day of the workshop, Dr. Wu Shih-Yin from the Taiwan Bamboo Orchestra and the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources of the National I-lan University Taiwan (ROC) lectured on the basic principles of bamboo instrument making. The participants were then introduced to the DOST-FPRDI, including a tour of the beautiful facility of the BMI Processing Center by Forester Aralyn Quintos, the BMI Program Leader from DOST-FPRDI. The instrument they were tasked to make for day one was a set of tongatong (bamboo stamping tubes). Longer tubes produced lower pitched sounds.

Ben, who is also a Music Education graduate, shares his observation about teachers in the workshop, “To see teachers very eager to learn instrument making gives me hope that indigenous music teaching is still far from dead. Even though the supply of readily available instruments for schools is low, teachers are willing to make [instruments] from scratch.”

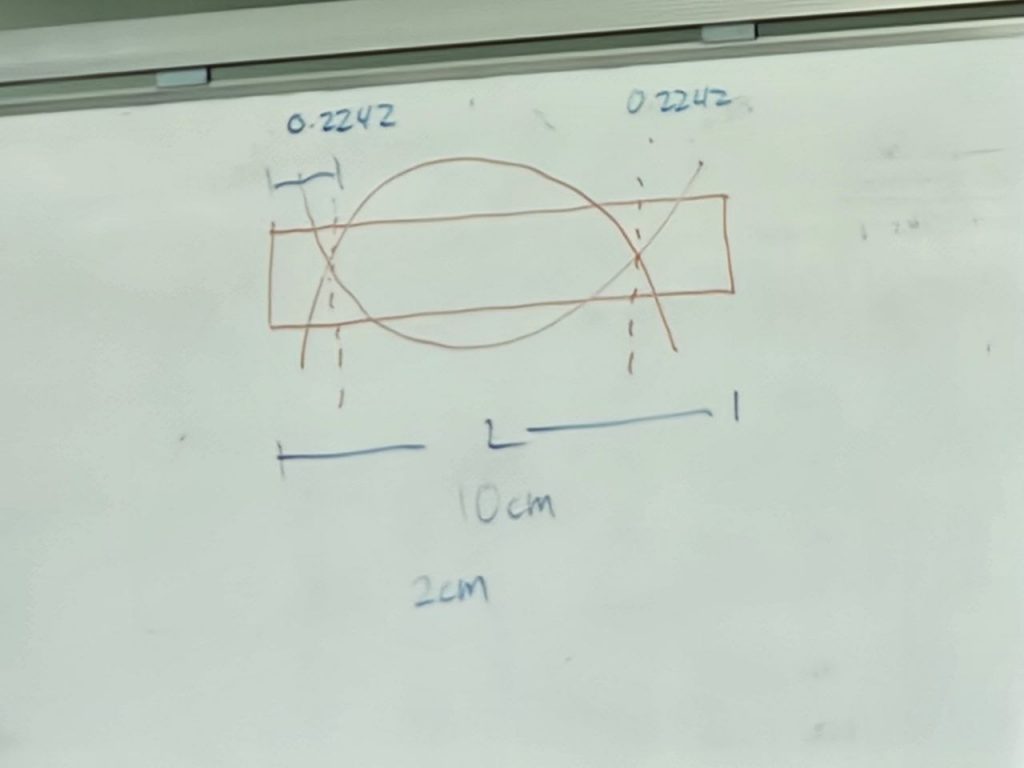

On the second day, the instrument to be made was the gabbang (type of xylophone). The different colors of the gabbang slabs were due to the thermal modification applied on the bamboo. With ready-made blades, they focused on learning how to tune through the instructions of Dr. Wu and other team leaders. As with the tongatong, shorter blades produced higher pitched sounds as compared to longer ones. The thickness of the blade also impacted the pitch – thinner blades produced lower pitches.

In the afternoon, they learned to make more instruments. They were tasked to make the two instruments of similar construction – the patangguk (quill-shaped tube), and the angklung (tuned bamboo tubes attached to a frame). Tuning these instruments proved difficult for most groups because it involved a more complicated two-step process of balancing the tuning between the blade and the tube parts, utilizing both tuning techniques required in making the tongatong (tube tuning) and the gabbang (blade tuning). Sharp ears are necessary in ensuring these are tuned properly. As Ben shared, “making an angklung is very hard work. The expensive prices of angklungs are justified. We almost gave up making just one [piece]. We could not tune it”. Aside from the tuning, James shared his experience, “mahirap siya sa pisikal na aspeto, lalo na sa mano-manong paglalagari,” (It is physically difficult, especially with regards to manual sawing).

Despite the difficulty involved, James and Ben found that the process of making instruments was improved with the marriage of science and traditional instrument making – a fusion of tradition and modernity. James said that the scientific methods made instrument making easier, which is different from what he observed in the traditional communities. “Naisip ko na mahabang praktisan ito sa mga lugar kung saan wala silang ganitong konsepto at base lamang sa mga tantsahan at karanasan sa kani-kanilang kultura,” (I realize that this will take a lot of practice in places wherein they do not have this concept, based only on approximation and experience in their own cultures).

On the third day, the participants needed to finish their instruments and rehearse for the closing program. The UPCE team, James and Ben, led the rehearsals on how to perform on the tongatong and patangguk. Another participant led the rehearsals for the gabbang and angklung.

A final lecture-workshop was given by composer Alexander John Villanueva, faculty from the UP College of Music Department of Composition and Theory, which involved enlisting the creative ideas from the participants themselves, producing patterns that can be performed by everyone.

The closing program was lively with the performances from the participants. All instruments made during the workshop were given to them to take home as a gift and remembrance. A successful, fruitful, albeit challenging workshop

According to James, the experience of being in the workshop was unique as he grew up interested in tinkering with things. With his assignment in the UPCE Instrumentarium, the new skills he gained through the workshop helps in how he can care more for the instruments in the collection, particularly the bamboo ones. He remarked that the instruments in the center were old as they were mostly gathered during the Ethnomusicological Survey done by the late National Artist Dr. Jose Maceda and his team of researchers that was started in the fifties.

Ben reflects on the impact the workshop had on his professional work in the Audio Conservation Laboratory, “even if I’m mainly working on the audio and digital materials of the archive, I feel that it adds to the knowledge of what the Center’s collection of recordings are, what they are, why they sound like that, how to make it sound like that, and more.”

As a graduate of Asian Music and Musicology, James shared how the workshop enriched his experience, “May mas malalim na pag-unawa na tungo sa instrumentong aking ginagamit at tinuturo, hindi na lamang sa konteksto ng pagtugtog at kung para saan ba ito tinutugtog, naroon na ang kultural na kaalaman kung paano ito ginagawa, paano ang proseso na nakapaloob dito,” (There is a deeper understanding towards the instruments that I use and teach, not just in the context of playing them and for what these are played for, but also having the cultural knowledge on the process of how it is made).

The trainings conducted by the BMI program truly contributes not just to the body of knowledge on bamboo musical instruments in the Philippines, but also paves ways for these to be applied in local communities and equip our teachers. This ensures that the bamboo music traditions that we have are sustainable, practical, and memorable. It is exciting to see how all of these efforts will continue to change and spread the beauty of bamboo music not just in the Philippines but beyond.

Learn more about The BMI Processing Center here.

See hightlights from the event below.

Related Articles